…she has an original Parker Brothers map of the world.”

This was interesting, since the map represented the only view we had of the world before the Something That Happened. For some reason, its destruction had not been demanded under Annex XXIV.

“Does she adhere to the theory that it represents global Chromatic regions of the pre-Epiphanic world?”

“She does, although I’m doubtful myself. If we were regionally blue when Something Happened, there’d be more evidence of it now.”

“And the RISK acronym? What does she think that stands for?”

“Regional International Spectral Kolor . Yes, I know,” Mr. Lemon-Skye agreed when I looked doubtful, “it must be an archaic spelling. But get her to show you the map. It’s almost complete, you know-only the nations of Irkutsk and Kamchatka have been eaten by clodworms.”

Jasper Fforde , Shades of Grey

Si la représentation de l’histoire dans les jeux de société est un sujet de débat assez fréquent, l’usage très particulier qu’ils font de la géographie n’a jamais vraiment donné lieu à réflexion. Les auteurs de jeu sont pourtant, après les géographes, parmi les plus gros utilisateurs de cartes. Qui plus est, ils ne se satisfont généralement pas des cartes dressées par les géographes et dessinent les leurs, se souciant souvent plus de jouabilité que d’exactitude.

Les cartes utilisées par les concepteurs de jeux de société sont essentiellement de quatre types que j’appellerai, par analogie, les parcours, les puzzles, les réseaux et les grilles.

Les parcours sont faits d’une suite plus ou moins linéaire de cases, constituant soit un trajet de la case départ à la case d’arrivée, comme dans le Jeu de l’Oie ou dans mon Pony Express, soit un circuit fermé comme dans les jeux de course automobile, ou dans le Monopoly. Dans un jeu de course comme Formule Dé, la dessin des circuits peut être assez fidèle, dans d’autres, comme le Monopoly, la pertinence géographique n’est même pas recherchée puisque c’est leur valeur immobilière, et non leur proximité, qui fait que certaines rues se retrouvent à côté d’autres.

Pony Express a l’un des plus beaux plateau de jeu que je connaisse, mais sous l’apparence d’une carte, ce n’est qu’une simple piste, comme au jeu de l’oie.

J’imaginais Lost Temple dans les montagnes des confins du Cambodge et du Laos, là ou Malraux situe l’action de la Voie Royale… j’ai été un peu surpris par la mer ajoutée par Pierô, mon ami illustrateur.

Le parcours peut être déformé, trituré, agrémenté de courbes et parfois de raccourcis pour donner l’apparence d’un plan plus que d’une ligne, mais il reste une ligne, une piste disent souvent les joueurs, qui disposent généralement d’un pion qu’ils doivent amener du départ à l’arrivée, ou auquel ils doivent faire faire un certain nombre de tours de circuit.

Le parcours d’Ave César, sans doute le meilleur jeu de course publié à ce jour, avec ses couloirs de ravitaillement et ses virages serrés, devait clairement dans l’esprit de son auteur voir s’affronter des formule 1 et non des chars romains.

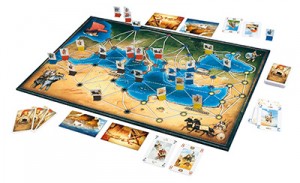

Le deuxième type traditionnel de cartes utilisé dans les jeux est la carte politique, qui prend la forme d’un puzzle dont les pièces sont coloriées en quatre ou cinq couleurs différentes – rarement moins, quatre couleurs étant le plus souvent nécessaires, et toujours suffisantes, pour colorer les régions d’une carte sans que deux régions voisines ne soient de même couleur.

Certaines de ces cartes peuvent être en tous points identiques aux cartes politiques des géographes ou, plus souvent, des historiens. En effet, si la géographie sert d’abord à faire la guerre, selon la célèbre formule d’Yves Lacoste, elle sert aussi beaucoup à jouer à la guerre. Diplomacy se pratique ainsi sur une carte politique parfaitement exacte de l’Europe en 1914. Souvent pourtant, dans les jeux de guerre comme le Risk, dans les jeux de majorité comme El Grande, dans des jeux mêlant guerre et commerce comme Mare Nostrum, l’auteur de jeu est amené à prendre des libertés avec la réalité politique. Sur la carte du Risk, les États-Unis et le Canada sont ainsi divisés en plusieurs cases pour faire de l’Amérique du Nord un champ de bataille plus conséquent et plus susceptible d’être divisé. La vaste Sibérie voit elle aussi apparaître des subdivisions, Irkutsk et Yakoutie, tandis qu’un vaste royaume de Siam semble quelque peu anachronique.

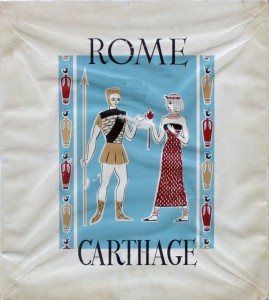

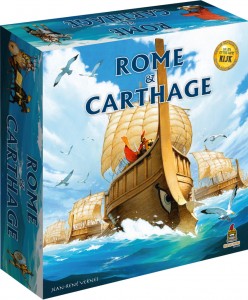

Les provinces romaines, royaumes et cités antiques de Mare Nostrum, comme de tous les très nombreux jeux centrés sur une carte de la Méditerranée, portent des noms authentiques, même s’ils ne sont pas nécessairement contemporains les uns des autres, mais sont surtout de superficies à peu près équivalentes, ce qui est bien plus pratique lorsqu’il s’agit d’y placer des armées et des marchandises.

Bien sûr, les univers imaginaires et fantastiques sont un bon moyen de contourner ces problèmes. Certains peuvent trouver à redire à tel ou tel détail de la carte d’Axis and Allies, nul ne peut reprocher la moindre inexactitude à celle de Conquest of Nerath.

Dresser une carte d’un continent imaginaire permet en outre de se concentrer sur l’intérêt ludique, ajoutant ici un large fleuve pour ralentir les armées ou accélérer le commerce, là une chaîne de montagne pour bloquer fermement tout passage autrement qu’à dos de dragon.

Personne ne viendra se plaindre de ce que la frontière entre Fullsome Pocket et Ellen’s Bight n’est pas bien placée.

Michael Menzel a réalisé de très nombreux plateaux de jeu panoramiques, pour Les Piliers de la Terre, L’Âge de Pierre, Andor et bien d’autres jeux…

Particulièrement intéressante sans doute pour les géographes comme pour les historiens est la carte de Viking Fury, réédité sous le nom d’Invasions. Si l’on est prétentieux, on peut y voir une tentative de représenter l’Europe “du point de vue des vikings”, mais il s’agissait sans doute pour les auteurs du jeu de dessiner l’Europe d’une manière qui permette de représenter les invasions vikings, quitte à prendre de nombreuses libertés avec la géographie physique. Le résultat est une étonnante carte un peu physique, un peu isochrone, un peu imaginaire.

Un autre exemple de parti pris étonnant est la carte de Trajan, certes un jeu assez abstrait. La carte présente l’Europe septentrionale et occidentale vue depuis Rome, en mode panoramique, à la manière des plans de stations de ski. Géographiquement surprenante, elle l’est aussi pour l’historien – alors que Trajan s’est surtout battu contre les Daces et les Parthes, et qu’on lui a parfois reproché de favoriser sa Bétique natale, ni la Dacie, ni les provinces hispaniques n’apparaissent sur la carte. Il est vrai que le jeu est surtout destiné à être vendu en Germanie.

Apparus dans les années quatre-vingt-dix, Les jeux de majorité sont un peu la version politiquement correcte des jeux de guerre. On ne s’y bat, pas on rivalise d’influence. On ne s’y tue pas, on s’expulse. Il y faut des cases peu nombreuses, une dizaine tout au plus, de préférence un peu irrégulières pour permettre des tactiques variées, et assez grandes pour que les intrigants des divers joueurs puissent y cohabiter.

La superbe carte d’El Grande, au style vaguement Renaissance a été dessinée par Doris Matthäus, qui a fait également celles, splendides, d’Elfenland, d’Elfenroads ou de Fugger, Welser, Medici.

Si Venise est particulièrement populaire parmi les auteurs de jeux, c’est sans doute parce que la ville fait rêver, mais c’est aussi parce que les canaux permettent de dresser très simplement les limites entre les quartiers.

Lorsque l’univers est assez vague, simplifié, symbolique, les régions prennent volontiers une forme géométrique, parfois carrée, notamment lorsque des cartes à jouer permettent de construire la surface de jeu, mais plus souvent hexagonale. Triangles, rectangles ou hexagones permettent tous de construire un dallage régulier d’une surface, mais l’hexagone est plus pratique. L’absence de contact par les coins facilite la conception de règles qui n’ont pas à définir précisément le caractère adjacent de deux régions, et les déplacements y ont un air moins rectiligne, donc moins abstrait, que sur un dallage carré. C’est le choix que j’ai fait dans La Vallée des Mammouths, où les six directions correspondent en outre au six faces du dé.

Des auteurs malins, comme Philippe Keyaerts, se sont même fait une spécialité des hexagones légèrement tordus ou déformés pour ne pas avoir l’air trop géométriques, comme dans Vinci ou Small World.

Antike, une carte où les frontières n’ont aucune pertinence géographique ou historique – il n’y a en fait que des hexagones.

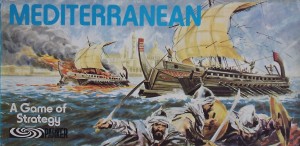

Le bassin Méditerranéen est sans doute la partie du monde la plus cartographiée dans les jeux. Si le style de la carte de Méditerranée est original, c’est que le thème n’est plus la guerre dans l’antiquité, mais le commerce à la Renaissance. Et l’on retrouve des hexagones, du moins en mer.

Les hexagones honteux peuvent même, comme dans Cyclades, se déguiser en cercles.

Certes, les géographes n’ignorent pas la géométrie, et le célèbre diagramme de Christaller sur les hiérarchies urbaines est fondé sur les mêmes propriétés mathématiques de l’hexagone. Mais pour les géographes, il s’agit là d’un schéma dont chacun sait qu’il ne décrit que très imparfaitement la réalité. Pour un joueur, c’est la réalité du jeu.

Summoner Wars se joue sur un tablier, nom que l’on donnait autrefois à tous les plateaux de jeu géométriques utilisés dans les jeux traditionnels. Pourtant, l’éditeur a ressenti le besoin de dessiner le quadrillage sur un semblant de carte, sans fonction particulière dans le jeu.

L’utilisation de formes géométriques permet aussi de construire un plateau de jeu modulaire. Les deux demi-plateaux recto verso de la Vallée des Mammouths permettent de construire quatre cartes, quatre terrains de chasse, de pèche et de guerre différents. Poussée à l’extrème, la modularité d’un jeu comme Les Colons de Catan, ou pour prendre des exemples plus récents Kingdom Builder ou Archipelago, permet de renouveler presque sans limite un jeu en assemblant différemment les éléments du plateau de jeu.

Dans Tikal, Entdecker ou Carcassonne, les joueurs construisent la carte – et le territoire – au fur et à mesure du jeu, ce qui n’est pas toujours très thématique.

Les cartes en réseau, encore rares il y a une vingtaine d’années, sont aujourd’hui aussi répandues dans les jeux de société que les cartes politiques en puzzle. Ici, la carte ne dessine pas des frontières mais des liaisons entre des points sous forme de chemins, de routes, dans Elfenland ou Isla Dorada, de voies ferrées, dans Les Aventuriers du Rail, de lignes aériennes, dans Airlines, ou même de lignes à haute tension dans Megawatts. Dans certains jeux de trains, ce sont même les joueurs qui dessinent le réseau sur la carte avec des feutres effaçables.

Même si l’action de beaucoup de ces jeux se déroule dans un lointain passé ou dans un univers féerique, ou pour les jeux de train au XIXème siècle, période de construction des grands réseaux ferrés, je ne peux m’empêcher de penser que la popularité récente de ces jeux “de réseau”, qui n’ont rien à voir avec les jeux en réseau, est liée à l’importance croissante attachée par nos sociétés modernes à l’idée de mobilité, et au relatif désamour pour les territoires, devenus un peu ringards. Il reste certes à expliquer pourquoi, même et surtout aux États-Unis, pays emblématique de l’automobile, les joueurs préfèrent les trains. Quoi qu’il en soit, en train, en voiture, en avion, le héros libéral hypermoderne ne conquiert pas, il voyage. En France, la distance à Paris ne se mesure plus en kilomètres mais en heures de train.

Le plateau d’Elfenland, remarquablement dessiné par Doris Matthäus, ressemble à une carte gravée de la Renaissance, avec les couleurs en plus.

J’ai dû modifier un peu le projet de carte d’Isla Dorada afin de regrouper les routes de montagne, désert et forêt dans les mêmes régions, et de rendre la carte plus cohérente. Ce n’est qu’après que Gorg a eu illustré la carte que j’ai réalisé qu’il y manquait un volcan.

Dans Inca Empire, la carte représente à la fois les régions et le réseau routier de l’empire inca. Quatre couleurs sont toujours suffisantes pour représenter les régions d’une carte de type puzzle sans que deux régions adjacentes par un côté ne soient de la même couleur.

Là encore, le souci de jouabilité peut souvent l’emporter sur celui d’exactitude. Les lignes ferroviaires représentées sur les diverses cartes des Aventuriers du Rail correspondent plus ou moins aux grandes lignes des années 1900 – mais plus ou moins seulement. Certaines villes peuvent même être quelque peu déplacées pour les besoins du jeu. Sur la première carte de Ticket to Ride, des joueurs américains se sont ainsi plaint que Duluth ait pris la place de Minneapolis. Duluth étant le grand nœud ferroviaire du Nord des États-Unis (et accessoirement l’un des meilleurs romans de Gore Vidal), cette cité ne pouvait pas être absente de la carte, et l’équilibre du jeu imposait de la déplacer un peu. De tels bricolages sont plus nombreux encore sur la carte européenne.

Je ne connais pas bien le réseau ferré suisse, mais je me suis laissé dire que la carte de la Suisse était la plus fidèle de toutes celles publiées à ce jour pour les Aventuriers du Rail.

L’excellente série des 10 Days in… , bien que jouée sur de bonnes vieilles cartes politiques, illustre elle aussi cette importance croissante du thème du voyage, de la mobilité, dans les jeux de société. Ce sont à ma connaissance les seuls jeux dans lesquels la carte géographique sert uniquement de référence, sans que l’on y place le moindre pion. Ces cartes sont donc des cartes politiques, et rien ne semble s’opposer à ce qu’elles soient rigoureusement exactes, et ce d’autant plus que les jeux se veulent vaguement éducatifs. Pourtant, dans 10 Days in Asia, j’ai été un peu surpris par les parcours des voies ferrées, originalité de cette édition, qui relient certains états. Je ne connais guère le réseau ferré asiatique, mais une rapide recherche sur internet a confirmé mon intuition : les lignes ferroviaires figurant sur le plateau de jeu n’ont rien en commun avec la réalité du réseau ferré, et ont donc été dessinées uniquement pour des raisons d’équilibre du jeu, pour rendre l’accès à certains états plus faciles. Je le regrette un peu, et aurait sans doute préféré un jeu moins équilibré joué sur une carte plus exacte.

Un exemple extrême: les lignes de bus représentées sur ce plan de Paris n’ont absolument rien à voir avec le réseau de la RATP. Paris Paris était un jeu abstrait, qui a été ensuite plaqué sur un plan de Paris.

En revanche, le réseau du London Underground dans Scotland Yard, un classique du jeu de déduction, est incomplet mais exact.

Tout comme celui de Metro 2033, jeu de science fiction russe dont l’action se déroule dans le métro de Moscou, et dont le plateau de jeu reprend le style graphique des plans du réseau.

Un plateau de jeu n’est pas qu’une carte que l’on regarde, on y place aussi des pions, on les déplace, on s’y bat ou on y fait la course, et dans un puzzle comme dans un réseau, cela entraîne des contraintes particulières. À l’heure d’Internet et des guerres informatiques plus ou moins fantasmées, il est d’ailleurs étonnant que les cartes réseau ne servent qu’à se déplacer, la guerre se jouant toujours sur de bonnes vieilles cartes puzzle.

Les Colons de Catan sont un bon exemple des tendances actuelles en matière de représentation cartographique dans les jeux. On y trouve en effet à la fois des régions hexagonales, et une structure en réseau utilisant les côtés et les angles de ces hexagones, sur lesquels les joueurs bâtissent routes et cités.

Un autre type de cartes, que les joueurs appellent parfois, très significativement, géomorphiques, ressemblent à des cartes classiques de géographie physique relativement exactes, sur lesquelles est appliquée une grille orthogonale ou, plus souvent, hexagonale. Les jeux de guerre, notamment, font fréquemment appel à cette technique qui n’est alors qu’un outil pour représenter clairement les positions des unités sur la carte géographique, et mesurer les distances de tir ou de déplacement. Tout juste la nécessité que chaque case soit clairement et entièrement de montagne, de plaine, de forêt, de lac ou de marais, et que les rivières coulent sagement entre les hexagones, amène-t-elle à prendre parfois de très légères libertés avec la géographie. Les joueurs de jeux de figurines, eux, jouent même sur de véritables cartes, voire sur des maquettes en trois dimensions, et mesurent les distances de déplacement et de tir à l’aide de règles et de mètres rubans.

Age of Steam, où l’on construit des réseaux sur une grille d’hexagones, ce qui relativise pas mal ma savante classification.

Esthétiquement, les cartes de jeu essaient parfois d’avoir le style graphique associé à l’époque décrite par le jeu. Pour représenter les guerres de l’antiquité, on choisira un style sobre, comme dessiné sur un papyrus ou gravé sur une tablette. Pour les guerres ou le commerce de la Renaissance, on imite les gravures sur bois, et on abuse des caractères gothiques, etc…

Et une carte qui semble réellement d’époque, et tromperait sans doute quelques historiens, pour rejouer la guerre américano-canadienne de 1812.

Parfois, le graphisme est vraiment raté, comme pour la carte du Yorkshire dans Last Train to Wensleydale, qui fait plutôt penser à la vue en coupe d’un poumon de troll.

C’est également vrai des lieux et des ambiances exotiques. Une carte du Japon aura souvent un look un peu japonisant, une carte du Moyen Orient un style arabisant, mais toujours dans un exotisme parfaitement assumé.

Une carte du japon magnifiquement réalisée : toute en hexagone, d’une clarté limpide, et dans un style qui, en Europe au moins, semble très japonais.

Si l’on veut rire un peu avec la cartographie ludique, c’est à la science fiction qu’il faut s’intéresser. Dans Mission Planète Rouge, La planète Mars est divisée en une dizaine de régions dont les noms ont été choisis parmi ceux que les scientifiques ont donné aux zones qu’y dessine la géographie physique – même si un correcteur orthographique facétieux a transformé Vastitas Borealis, les vastes plaines du nord, en Vasistas Borealis, la petite fenêtre du Nord. Ce n’est pourtant pas là l’erreur n’a plus notable. La Mars de Mission Planète Rouge n’est en effet pas une sphère mais un disque, plat, avec des régions sur sa circonférence et d’autres en son milieu.

Mars,un disque rouge flottant dans l’espace, avec trois régions intérieures et sept régions extérieures dont, au Nord (c’est à dire en haut…) la mal nommée Vasistas Borealis.

Rien d’étonnant d’ailleurs à cela puisque une rapide enquête parmi d’autres jeux de science fiction montre clairement que, de Twilight Imperium à Éclipse, en passant par tous les jeux de conquête, de découverte ou d’exploration spatiale qui semblent revenir à la mode ces temps-ci, c’est généralement tout l’espace qui est plat, réduit à deux dimensions. Plus étonnant encore, c’est aussi très souvent le cas dans les jeux informatiques, alors même qu’une modélisation en 3D est aujourd’hui tout à fait possible. la restriction de l’univers à deux dimensions a bien sûr des raisons pratiques, la surface plane du plateau de jeu, mais elle a donc aussi peut-être des raisons cognitives, notre esprit effectuant mal, surtout sans support visuel, les triangulations (ou pyramidisations) nécessaires à la mesure des distances dans un espace en trois dimensions.

C’est une des raisons pour lesquelles je suis très fier de l’approche géographique choisie pour le plateau de jeu d’Ad Astra : tous les systèmes stellaires sont considérés comme équidistants, un passage par l’espace profond étant nécessaire pour aller de l’un à l’autre. C’est simple, et finalement plus réaliste qu’un espace plat, même figuré par une carte avec des milliers d’hexagones. Toutes les planètes d’un même système sont également équidistantes, et j’imagine assez mal un plateau de jeu avec des planètes qui tournent autour de leur soleil à des vitesses différentes, ne cessant de s’éloigner et de se rapprocher.

Le plateau de jeu est généralement le lieu de l’affrontement ou de la course entre les armées ou les pions des joueurs. Des limites techniques évidentes font que ce lieu est le plus souvent représenté par une surface plane, donc une carte ou plan. L’affinité entre cartes et jeux n’est cependant pas purement technique, elle a aussi une dimension plus psychologique. Les enfants le sentent bien, qui saisissent instinctivement la dimension ludique des cartes géographiques, et en font spontanément le support de jeux de guerre ou de voyage. La carte est une représentation volontairement simplifiée de l’espace réel, qu’il soit social ou physique. Le jeu est un système d’interactions sociales délibérément vain et simpliste. Rien d’étonnant à ce que le jeu prenne souvent appui sur la carte.

…she has an original Parker Brothers map of the world.”

This was interesting, since the map represented the only view we had of the world before the Something That Happened. For some reason, its destruction had not been demanded under Annex XXIV.

“Does she adhere to the theory that it represents global Chromatic regions of the pre-Epiphanic world?”

“She does, although I’m doubtful myself. If we were regionally blue when Something Happened, there’d be more evidence of it now.”

“And the RISK acronym? What does she think that stands for?”

“Regional International Spectral Kolor . Yes, I know,” Mr. Lemon-Skye agreed when I looked doubtful, “it must be an archaic spelling. But get her to show you the map. It’s almost complete, you know-only the nations of Irkutsk and Kamchatka have been eaten by clodworms.”

Jasper Fforde , Shades of Grey

The way history is represented in boardgames is very often discussed in gaming meetings and forums, but there has been very little thought on the specific use they make of geography, and geographic tools. Game designers are probably the biggest consumers of maps, of course after professional geographers. Even more, they usually don’t hold on maps drawn by geographers and draw their own, more concerned with “playability” than with accurateness.

Game designers use mainly four different kinds of map, tracks, puzzles, networks and grids.

Tracks are made of an ordered succession of spaces, or sometimes dots, usually creating either a single path from the starting space to the finish line one, like in the game of Goose or in my Pony Express, or a circular track like in Monopoly, or in most car racing games. In a racing game like Formula D, the representation of actual car racing tracks is very accurate, while in Monopoly the geographic accuracy was not even aimed at, since the cities are grouped by real estate values and not by region.

In my idea, Lost Temple was situated in the mountains on the Cambodge Laos border, where André Malraux placed the action of his novel The Royal Way. I was a bit surprised when I received a map with a large sea from the illustrator, my friend Pierô.

The track can be deformed, with add curves, sometimes even crossings and shortcuts, like in Snakes and Ladders, to look more like a plan than like a line, but it’s still basically one dimensional, the players usually having one single pawn that they must move from the start to the finish line, or a few times around the track.

The board of Ave Caesar, probably the best racing game ever designed, hassharp bends and stand stops. It was obviously designed as a car racing board and not a chariot one.

The second, and more frequent, kind of map is the traditional two-dimensional political map, which looks like a puzzle whose pieces are colored in four or five different colors – four colors are usually required, and are always sufficient, to color the different regions on a map without ever having two adjacent same-colored regions.

Some of these maps are perfectly identical with geographers’ or, more often, historians’ ones. If geography serves, first and foremost, as told Yves Lacoste, to wage war, it also serves to play war. Diplomacy is played on a perfectly accurate political map of Europe in 1914. However, in war games like Risk, in majority games like El Grande, in games with both war and trade like Mare Nostrum, the game designer often takes some liberties with the game’s geographical and historical setting. USA and Canada are divided in two or three spaces each on the Risk map, or even in the Axis and Allies one, to make for a more consequent, divided and competitive battleground. Risk has Irkutsk or Kamchatka look like Asian states, and a vast and somewhat anachronistic kingdom of Siam.

The Roman provinces and antique states in Mare Nostrum, and in all the many games played on a map centered on the Mediterranean, have historical names, though not necessarily contemporary one with the others, and are all of similar size, which is more convenient when placing armies or trade goods on them.

Both historians and geographers might be fascinated by the map for Viking Fury, and itsluxuous reissue, Fire and Axe. it can be pretentiously described as the world from a Viking point of view, but is more Europe and the Atlantic redrawn in a way to allow representation and play of the viking invasions, at the cost of strong deviations from actual geography. The result is a strange map, part physical, part isochrone, part fantasy.

Trajan is a very abstract boardgame with a very figurative map. It represents western and northern Europe viewed from Rome, a panoramic picture drawn like ski resorts maps. It’s geographically original, but also historically surprising. Trajan fought mostly against Dacians and Parthians, and has been suspected of valorising his native province, Baetica. Neither Dacia nor Hispania are on the map – but the game is mostly to be sold in Germania.

Imaginary and fantasy worlds are an obvious and easy way to circumvent geographical issues. One can find inaccuracies in the Axis and Allies map, but no one can find a single error in the Conquest of Nerath one. When drawing the map of an imaginary land, one can focus on playability, adding a wide river here to stop the armies or speed up the trade, a high mountain there to prevent any crossing unless on dragon’s back.

Noone will ever complain that the border between Fullsome Pocket and Ellen’s Bight has been misplaced.

One of the many games illustrated by Michael Menzel, who also designed the boards for Pillars of the Earth, StoneAge and many more.

Majority games appeared in the nineties, and are a kind of politically correct version of war games. There’s no fight, just (more or less) pacific rivalry. It’s not about war, it’s about influence. These games need large boards with few spaces, usually less than a dozen, but large enough for the many wooden cubes or meeples from several players.

The Renaissance-like map for El Grande was drawn by Doris Matthäus, who also made the gorgeous maps for Elfenroads, Elfenland or Fugger, Welser, Medici.

There are lots of games played on maps of Venice. It might be because of it’s charm and history, but it’s also because canals are very convenient as borders between districts.

When the setting is vague, simplified, symbolized, regions often have a geometrical shape. Squares or rectangles were old favorites, and are still used, especially when the map is made of adjacent cards, but hexagons are more hype. Triangles, rectangles and hexagons can all be used to draw a regular grid, but hexagons have many advantages. There’s no problem with corner adjacencies, and movement looks less rectilinear, and therefore less abstract, than on a square grid. In Valley of the Mammoths, it has another advantage, the six sides of the hexagons corresponding with the six faces of a die.

Clever designers, like Philippe Keyaerts, sometimes draw hex grids and then twists the hexes a bit so that their maps don’t look too regular and geometric – see Vinci, Small World, even Olympos.

Probably the least accurate map of the Mediterranean. Borders are totally inaccurate, and all the regions are in fact hexagons.

The Mediterranean is probably the most cartographied place in games. Here the graphic style is different because, for once, the theme is not antique wars, but Renaissance trade.

Hexagons can even be disguised as circles, like in Cyclades.

Of course, geographers also use geometry, may be more than they should. The best known geographical diagram, Christaller’s central place theory, is based on the same properties of the hexagonal grid. For geographers, however, it’s an abstract diagram and they all know that reality is very different. For a gamer, it’s the game’s reality.

Summoner Wars is played on 6 x 8 checkered grid, but the publisher printed the grid on what looks like a map, or a battle plan, which has no particular use in the game.

Using geometrical shapes is also a good way to have modular maps, and therefore an ever different game. The two double faced half-boards of Valley of the Mammoths make for four different boards. More modular games like Settlers of Catan, or more recent ones like Archipelago or Kingdom Builder, have almost unnumerable ways of assembling the boatrd elements in different maps.

In Tikal, Entdecker or Carcassonne, players build the map – and the territory – while playing the game. Not always logical, not always thematic, but very interesting.

Network maps were very rare twenty years ago, but they are now used in boardgames almost as often as puzzle maps. A network track doesn’t have borders and regions, it has dots – usually cities – and tracks between them. These tracks can be roads, like in Elfenland or Isla Dorada, railway lines, in Ticket to Ride, Airlines in… Airlines , and even electric lines in PowerGrid. In the so called “crayon train games”, the players even draw the map on the board during the game with erasable markers.

Even when the action in most of these games takes place in ancient history or in fantasy settings, and for train games in the XIXthe century, when most train networks were initially built, the recent popularity of network maps in boardgames is probably due to the increased social focus on the idea of mobility in the modern world, and the relative disaffection for territories. Interestingly, especially in the United States, where everyone moves by car and by plane, games are more often about trains. Anyway, by train, car or plane, the hypermodern hero doesn’t conquer any more, he travels. In France, distance from Paris are no more in kilometers, they are in hours, usually by train.

I had to change the map design for Isla Dorada to group the desert, mountain and forest path in the same regions and make the map more consistent – and more spectacular. It’s only after the map was draw by Gorg that I realized it misses a volcano.

The Inca Empire map has both the districts and the road network of the Inca Empire. Four colors are always enough to color the pieces of a puzzle-map with no corner adjacency with no adjacent regions having the same color.

Once more, playability is more important than accurateness. The main tracks on the Ticket to Ride maps are more or less the big railway lines around 1900 – but nly more or less. Some cities have even be moved to make the board easier to use. There was much talk of the way Minneapolis has become Duluth on the original Ticket to Ride map. Since Duluth (by the way, my second favorite Gore Vidal’s novel) was one of the main railway lines nodes in the US, it had to be on the map, and the game balance imposed to move it a few miles. There are even more such approximations on the European map, and they don’t detract from the game.

I don’t know the Swiss rail network well enough, but I’ve been told the Switzerland map is the most accurate of all the Ticket to Ride maps.

The outstanding game series 10 Days in… is played with good old political maps, but also emphasizes the increasing trend of mobility and travel in boardgames. The 10 Days in… games are, as far as I know, the only one requiring a map on which no pawn or token is ever placed, and there seems to be no reason for it not to be perfectly accurate, especially when it also vaguely claims some educational value. When playing 10 Days in Asia, though, I was surprised by the tracks of the railway lines, which are the special feature of this map. I didn’t know anything about the Asian rail network, but I had no difficulty finding several maps of it – geographical maps – on the internet, and found out that the railway lines in the game have nothing to do with actual ones, and have probably been drawn only to balance the game and make some counties easier to reach. I would have preferred a more accurate map, even when less balanced.

An extreme example : The network in Paris Paris has nothing in common with actual bus lines. This was an abstract game, whose regular shape has been pasted on a map of Paris.

On the other hand, the underground network in Scotland Yard, a classic deduction game, is uncomplete but accurate.

And the same is true of the map of Metro 2033, a russian science fiction game whose action takes place in the Moscow undergound. The game board graphic style is directly inspired by the underground network map.

A game board is not just a map one looks at, it’s a map on which one moves trains, trades goods, fight wars, and this means specific constraints, no matter whether one designs a puzzle or a network map. In the age of the internet, and of fantasized (and probably real as well) computer wars, it’s surprising than war is still always played on good old political maps, with lots of borders and no information highways.

Settlers of Catan is a very good example of modernboardgame cartography. It has large hexes of plain, forest or mountains, but also makes use of the hexes edges and corners, where players build a network of roads and cities.

Geomorphic maps are also sometimes used in games. These are realistic and accurate maps with most of the landscape elements represented, on which an orthogonal or, once more, hexagonal grid is superimposed. Wargames and other simulation games often use such maps. The grid is just a tool to represent where the units are supposed to be in the “real world” and to measure movement and firing range. The necessity for each hex to be clearly either forest, or mountain, or sea, and for rivers to roll between hexes, make for very minor adjustments to relief reality. Miniature wargamers even play on regular maps, of even on 3D maps, measuring distances with rulers.

Age of Steam, or building networks on an hex grid, and making all my carefully devised categories fall apart.

Illustrators often try, if not to copy old cards, at least to imitate the style of the period when the game’s action is supposed to take place. Antique war maps are drawn on papyrus or carved in stone. Mediaeval wars and trades are played on cards looking like wooden engravings, and all names are in gothic fonts.

And a map that looks very historical, and could even deceive historians, to play the USA-Canadian war of 1812.

Sometimes, the graphics go completely wrong, like in the Yorkshire map in Last Train to Wensleydale, which looks more like a troll’s lung cross-section.

Of course, this is also, though less systematically, true of exotic settings – maps of Japan often try to look japanese, maps of China to look Chinese, maps of the Middle East to look arabic, though never in a very convincing way – the exoticism is perfectly assumed here.

A very well designed map of Japan : it’s all hexagons, it looks Japanese enough, and it’s very clear and neat.

The real fun in boardgame cartography, however, comes with science fiction. In Mission: Red Planet, Mars is divided in a doyen régions whose names are those of real Martian relief features – even when some facetious spelling corrector changed Vastitas Borealis, the great northern plains, into Vasistas Borealis, the small northern window. The most notable inaccuracy, however, is that the actual planet is a sphere, not a disk with center regions and peripheral ones.

Mars, a flat disk with three inner regions and seven outer ones, including the misnamed Vasistas Borealis (north, meaning up on the map).

Well, may be this is logical after all, since in most science fiction boardgames, including very complex ones such as Eclipse or Twilight Imperium, and no matter whether they are about space exploration, conquest or empire development, the whole space is desperately flat, 2D. It’s even often the case in sophisticated online games, when computers are now powerful enough to design consistent 3D worlds. Restricting space to two dimensions is of course due to obvious technical reasons, the flatness of the game boards, but might also have cognitive ones, our minds having trouble making the necessary triangulations (or is it pyramidizations?) to asses distances in a 3D space without any visual support.

That’s one of the reasons why I’m quite proud of the way Serge Laget and I dealt with distance in Ad Astra : all sun systems are considered equidistant, and a movement through deep space is needed to move a spaceship from one to another. It’s simple, and more true than a flat space, even with thousands of hexes. All the planets in a given system are also considered equidistant – because we cannot have a board with perpetually rotating planets, whose distance from one another changes every round.

The game board is usually the place where the war or the race between the players pawns or tokens, armies or meeples, takes place. Because of obviousntechnical limitations, this place is most usually a flat board, therefore a map or plan. However, the affinity between games and maps is not only technical, it also has a psychological aspect. Children spontaneously use maps as support for games, games of war or of travel. Maps are deliberately simplified représentations of social or physical realities. Games are deliberately simplified systems of social interactions. It’s no wonder games can make use of maps.