2019 a été pour moi une année relativement modeste, avec seulement trois jeux publiés. Le Petit Poucet, avec Anja Wrede, sera le tout dernier de la belle série des Contes et Jeux, chez Purple Brain. Tonari, joliment édité par IDW, est une remise au goût du jour d’une vieille idée d’Alex Randolph. Animocrazy est une nouvelle version de Democrazy, publié par un éditeur de Hong Kong, Jolly Thinkers, dans une édition bilingue anglais-chinois Si les trois ont eu de bonnes critiques, je n’ai pas l’impression qu’ils soient de grands succès commerciaux.

Si tout se passe comme prévu, 2020 devrait être bien plus riche en nouveautés, avec une petite dizaine de jeux dans les tuyaux, même s’il est probable que quelques uns finiront, comme toujours, par prendre un peu de retard.

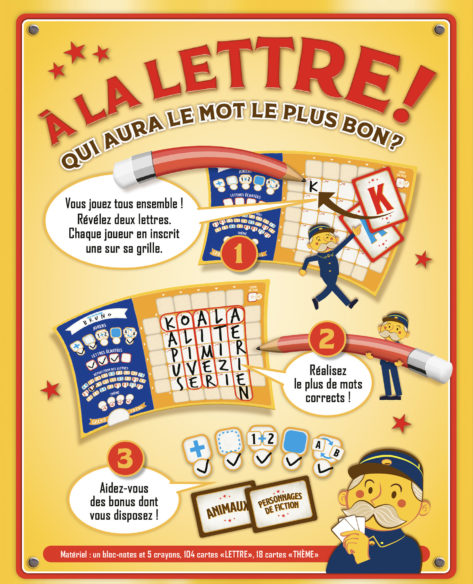

Les premiers arrivés seront tous de petits jeux de cartes, mais dans des styles bien différents. Dans Vintage, illustré par Pilgrim Hogdson et publié chez Matagot, les joueurs collectionnent, et à l’occasion volent, des objets des années 50, 60 et 70. Dans Poisons, conçu avec Chris Darsaklis, illustré par Marion Arbona et publié chez Ankama, les joueurs sont des nobles attablés à un banquet et désireux de boire le plus possible sans se faire empoisonner. Dans Stolen Paintings, chez Gryphon Games, ils sont voleurs d’œuvre d’arts ou détectives tentant de les retrouver. Dans Gold River, version revisitée de La Fièvre de l’Or, ce sont des chercheurs d’or durant la ruée vers l’ouest. Dans Vabanque, un très vieux jeu conçu avec Leo Colovini qui n’avait jusqu’ici été publié qu’en allemand et en japonais, ils jouent, bluffent et trichent un peu au casino. Dans Reigns – The Council, avec Hervé Marly, l’un d’entre eux est le roi, les autres sont des courtisans s’efforçant, comme dans le jeu sur téléphone, d’influencer les décisions. Maracas, avec le même Hervé Marly, est un jeu qui se joue avec une maracas – vous devriez deviner aisément qui est l’éditeur en regardant la photo.

Je n’ose plus donner de date pour Ménestrels, conçu avec Sandra Pietrini et joliment illustré par David Cochard, dont, après quelques années de retard, j’attendais la sortie en 2019. L’éditeur rencontre quelques difficultés, mais j’espère que le jeu finira par arriver – et si ce n’est pas le cas, on lui cherchera un nouvel éditeur.

La fin de l’année, si tout va bien, devrait voir arriver des projets plus ambitieux et plus inhabituels, et même une ou deux grosses boites de jeu comme je n’en ai plus publié depuis quelques temps, avec des vampires, des nains et des trolls, de l’or, des pierres précieuses et du métal. Mais ça, je vous en parlerai plus tard.

J’espère que, dans un marché un peu encombré, mes nouvelles créations vont se vendre un peu car, confronté à l’immense gâchis (pour parler poliment) de la réforme du lycée, j’envisage de plus en plus sérieusement, et un peu lâchement, de déserter l’éducation nationale. Si j’ai commencé l’enseignement un peu par hasard, c’est devenu une passion, mais cela ne peut en rester une que si je peux faire mon métier de prof honnêtement, c’est à dire enseigner des programmes qui ont du sens, dans des conditions correctes, et avec un minimum de liberté pédagogique. Tout cela ne va clairement plus être possible dans le cadre de la nouvelle organisation du lycée et du baccalauréat, qui brise en outre les solidarités entre enseignants et entre élèves auxquelles j’étais très attaché. Face à une réforme qui est au mieux un mélange absurde d’incompétence, d’improvisation et d’autoritarisme, au pire une stratégie délibérée d’humiliation et de précarisation subjective des enseignants, des élèves et des personnels de direction, beaucoup de profs sont désespérés et rêvent de s’en aller. Je suis l’un des rares à pouvoir se le permettre.

Abandonner l’enseignement impliquerait aussi de ne plus me consacrer qu’au jeu. Financièrement, ce ne devrait pas être un problème à court terme, même si je continue à penser que le marché du jeu a connu, ces dernières années, une croissance sinon artificielle, du moins trop rapide pour être durable. Entre la surproduction et la concurrence accrue, qu’elle soit en boutique et sur kickstarter, et des modes dans lesquelles je ne me reconnais pas toujours, je ne suis cependant pas certain d’être très à l’aise si j’essaie de m’impliquer plus avant dans le monde de l’édition… mais qui sait ! L’éducation m’apportait jusqu’ici un certain confort moral, le sentiment de faire un boulot qui a du sens, un boulot socialement utile, quand la caractéristique fondamentale du jeu, et celle qui fait tout son charme, est qu’il ne sert absolument à rien – mais il est vrai que c’est justement la perte programmée de ce sens qui me fait songer à quitter l’enseignement.

À propos des modes et tendances qui m’énervent un peu…. Je ne suis pas résolument hostile à Kickstarter, je suis même plutôt bon client et pense que cela va rester, mais je n’aime pas, quand l’un de mes jeux s’y retrouve, devoir faire la promotion de la campagne sur twitter et Facebook de manière un peu trop appuyée. Les jeux hybrides me semblent plus souvent le cul entre deux chaises que le meilleur des deux mondes, même si cela va peut-être s’arranger. Alors même que, dans les années quatre-vingt, j’avais bien aimé les livres dont vous êtes le héros, les Escape game en boîte (et ceux en vrai aussi) me font plus l’effet de casse-tête que de jeux de société. Les jeux Legacy demandent bien trop de temps et de régularité pour que j’y joue, bien trop de temps et de travail pour que j’essaie d’en concevoir. Pour compenser cela, Horrified et Pandemic – Fall of Rome m’ont un peu réconcilié avec les jeux coopératifs.

Si je râle un peu contre quelques modes, je constate cependant qu’il n’y a jamais eu autant non seulement de nouveaux jeux, mais surtout de bons voire d’excellents jeux publiés. Voici donc un petit choix parmi mes découvertes de cette année – mais il y a sans doute des jeux tout aussi bons, voire meilleurs, parmi tous ceux auxquels je n’ai pas joué.

Mr Face de Jun Sasaki et Selfie Safari de David Cicurel sont deux petits jeux d’ambiance sur les visages, aussi idiots que rigolos, et qui marchent toujours. Le second est d’ailleurs un jeu hybride, chaque joueur ayant besoin d’un téléphone, ce qui montre que je n’y suis pas totalement réfractaire. De la cafetière viennent deux autres petits jeux d’ambiance rigolos, Super Cats et Ninja Academy, j’ai même remporté un petit concours où il fallait imaginer une carte d’extension pour ce dernier. La même équipe, ou à peu près, a conçu le plus sérieux mais encore assez rapide Draftosaurus. Oriflamme, de Adrien et Axel Hesling, a tout d’un jeu de Bruno Faidutti, avec ses cartes tantôt cachées, tantôt visibles, et qui parfois se déplacent. Die Quacksalber von Quedlinburg, de Wolfgang Warsch – Les Charlatans de Beaucastel en français – est un excellent jeu familial à l’allemande, qui mêle agréablement chance, prise de risque et planification – pour les pros, c’est du « bag building ». Flick of Faith, de Paweł Stobiecki, Jan Truchanowicz and Łukasz Włodarczyk, est un adorable jeu de pichenettes et de majorité avec votes et pouvoirs spéciaux, mélange improbable mais léger et très réussi. Scorpius Freighter, de Mathew Dunstan et David Short, est un jeu de pick-up and deliver particulièrement chafouin, pour utiliser un adjectif cher à l’autre Bruno, et malheureusement passé totalement inaperçu. Il fallait un jeu japonais dans la liste, c’est Master of Respect, de Kentaro Yazawa, un très dynamique et très mignon jeu de gestion d’une école d’arts martiaux – pourquoi pas ! Hadara, de Benjamin Schwer, est tellement fluide, bien conçu et bien édité qu’il m’a réconcilié avec un genre que je n’appréciais plus guère, les jeux de gestion de ressources allemands un peu froids et abstraits. Res Arcana, de Tom Lehmann, m’a quant à lui réconcilié avec les jeux de cartes à combinaisons tarabiscotées, même s’il reste un peu trop technique pour mon goût. Dans la même catégorie, mais bien plus légers quand même, j’ai aussi beaucoup aimé Abyss Conspiracy, de Bruno Cathala et Charles Chevallier, même si je n’en comprends ni le thème, ni le graphisme, ainsi que Nine, de Gary Kim. Horrified, de Prospero Hall, très américain, un peu baroque et pas trop au sérieux, est un jeu de coopération très agréable, même pour ceux qui, comme moi, n’apprécient pas trop le genre. Je ne pratique pas non plus beaucoup les jeux à deux, mais j’ai vraiment adoré Nagaraja, de Bruno Cathala et Théo Rivière, beaucoup plus agressif qu’il n’en a l’air.

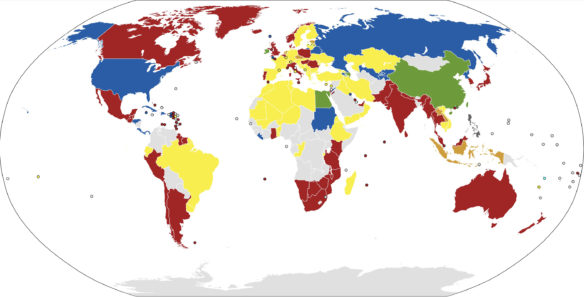

La fréquentation de ce blog baissait depuis quelques années, et était passé en 2018 sous les 300 visiteurs par jour. En 2019, avec une actualité personnelle pourtant moins fournie, les visites sont redevenues plus nombreuses, ce qui m’encourage à continuer à écrire ici. Le nouvel article le plus visité a été celui sur la scène ludique iranienne, Jouer à Téhéran. Viennent ensuite un article déjà ancien, Décoloniser Catan, puis la présentation de mon jeu Kamasutra – mais dans ce dernier cas, je soupçonne des moteurs de recherche facétieux.

Ceci était la première et la dernière fois que je formatais et postais un article de blog entièrement sur mon ipad. C’est sûrement plein de fautes, et j’espère que c’est lisible sur un ordinateur….

2019 has been a modestly productive year for me, with only three games published. Lost in the Woods, designed with Anja Wrede, is the very last in the Purple Brain’s Tales and Games series. Tonari, gorgeously published by IDW, develops an older Alex Randolph’s design. Animocrazy is new version of Democrazy, in a bilingual Chinese / English edition by Hong Kong publisher Jolly Thinkers. All three got good reviews, but I don’t think they’ve been real hits so far.

If everything works as scheduled, I should have many more new designs in 2020, about ten, even when, as usual, a few ones will certainly be delayed. First will come several light games, in very different styles. In Vintage, published by Matagot with art by Pilgrim Hogdson, players sell, collect and occasionally steal vintage items from the 50s, 60s and 70s. In Poisons, designed with Chris Darsaklis, illustrated by Marion Arbona, and published by Ankama, they are nobles at a banquet, trying to drink as much as possible while avoiding getting poisoned. In Stolen Paintings, published by Gryphon Games, they are art thieves or detectives trying to find the stolen paintings. In Gold River, a modernized version of Boomtown published by The Lumberjacks, they are gold diggers during the gold rush. In Vabanque, an old co-design with Leo Colovini which had so far been published only in German and Japanese, they’re bluffing their way to riches in Casinos – unfortunately, I’m afraid the new version will be only in French ! In Reigns – The Council, with Hervé Marly, one of them is the king and the other ones are courtiers and advisors trying to influence his decisions, just like in the phone game. Maracas, designed with Hervé Marly, is a game played with a (special) Maracas. You should guess who the publisher is from looking at the picture.

I won’t give any more publishing deadline for Minstrels, designed with Sandra Pietrini and gorgeously illustrated by David Cochard. It has already been delayed a few times, but I really expected it to be published in 2019. The publisher has some problems, but I still hope the game will be there soon. If it really doesn’t work, we’ll look for another publisher.

I ought to have more ambitious designs, some of them in big boxes, at the end of the year. Big boxes with vampires, dwarves and trolls, with gems, gold and metal. More about it in a few months.

I really hope that, in a an already overcrowded market, some of my new games will sell well because I’m seriously, and a bit cowardly, considering quitting my daily job, as an economics and sociology teacher. The French high school reform which started to be implemented this year is absolutely catastrophic. Many French high school teachers would like to quit, I happen to be among the few ones who can afford it. More details about it in the French text, I don’t think my english speaking readers will be much interested in this.

Of course, quitting teaching would mean devoting all of my working time to boardgames. Financially, I can afford it, at least in the short term, even when I still think the boardgame market growth these last years has been if not artificial, at least too fast to be sustainable much longer. Overproduction leads to increased competition, both in shops and on kickstarter, and while I like competition in gams, I don’t like it in real life. There are also a few recent trends I don’t necessarily like. That’s why I’m not sure I would feel at ease if I were to invest more time and energy in the game publishing business… but who knows ! Teaching is providing me with moral comfort, with the knowledge that I’m doing a meaningful and useful job, while the very essence of games, and what makes their charm, is that they are totally devoid of meaning or utility.

Here are some of the recent trends I’m wary of. I don’t really dislike Kickstarter. I think it’s here to stay, and I’m even a compulsive pledger, but I dislike having to support a campaign for my own games, posting too often and too aggressively on Twitter and Facebook. I think hybrid games usualy don’t bring the best of both worlds but fall between two stools – though I have hopes this will slowly improve. In the eighties, I really enjoyed reading choose your own adventure books, but I’m now bored by most « escape rooms in a box » – and in fact by most escape rooms, which feel more like puzzle than like games. Legacy games require too much time, dedication and regularity to play, too much time, dedication and work to design. At least, this year, the excellent Horrified and Pandemic – Fall of Rome made me reconsider my old hostility to cooperative games.

OK, I play the old boomer and rants against some trends, but I’m also impressed by the number not only opf games, but of outstanding games published now. Here comes a short list of my 2019 discoveries, but there are probably even better games among the hundred ones I’ve not played.

Jun Sasaki’s Mr Face and David Cicurel’s Selfie Safari are two fun party game about faces, fun and stupid, which work with everyone. The latter is a hybrid game, since every player needs their phone, which proves I’m not totally hostile to the genre. The coffee machine team has designed two other fun light party games, Super Cats and Ninja Academy – I even won an expansion card design contest for the latter. They also designed the more serious, though still fast paced, Draftosaurus. Adrien and Axel Hesling’s Oriflamme feels very much like one of my own designs, with its face up and face down cards – no wonder I enjoyed it a lot. Wolfgang Warsch’s The Quacks from Quedlinburg is your typical middle weight German family game, but it’s a really good one with the right mix of luck, programming and risk taking – it’s what pros call a « bag building » game, as if one could build a bag. Flick of Faith, by Paweł Stobiecki, Jan Truchanowicz and Łukasz Włodarczyk, is a really fun and light flicking / majority games with special powers and even some voting, on a fun and provocative theme, rival religions. Matthew Dunstan & David Short’s Scorpius Freighter an intricate pick-up and deliver game about space smugglers – which might explain why it went largely under radar. I had to put a Japanese game in this list, it’s Master of Respect, by Kentaro Yazawa, in which players are rival old masters of martial arts trying to form the best students – why not… Benjamin Schwer’s Hadara is a heavy German resource management game, a genre I’m supposed to be tired of, but it’s so fluid, well designed and well published that I really enjoyed playing it – even when I still have no idea what its theme is. Tom Lehman’s Res Arcana reconciled me with combo card games, even when it’s still a bit too technical for me. I’m more likely to play lighter games such as Bruno Cathala and Charles Chevallier’s Abyss Conspiracy – even when I don’t understand its art and setting – or Gary Kim’s Nine. Horrified, by Propspero Hall, is an american style game, slightly baroque and not too serious, extremely enjoyable, even by one who usually doesn’t care for cooperative gaming. I also don’t play many two player games, but I really enjoyed Nagaraja, by Bruno Cathala and Theo Rivière, which is much more interactive than it first looks.

This blog’s visiting figures were declining for a few years, and went for the first time under 300 visitors daily in 2018. In 2019, even though I had fewer new games, it started to go up again, which means it still makes sense to post long articles here. My most visited blogpost was Boardgaming in Tehran. The next ones are older stuff, first my long essay about Postcolonial Catan, then the presentation of my Kamasutra game. I suspect this last one is due to mischievous search engines.

This was the first and last time I entirely wrote, formatted and posted a blogpost entirely from my iPad. I’ll never do it again.